Guest Blog: Mental Health and Complex Grief in Survivorship

Rachel McCallum is a long-term survivor diagnosed with Anaplastic Astrocytoma of the 4th ventricle of the brain stem in 1993. Her experience as a long-term survivor has encouraged her to become an advocate for others like herself who have struggled with the transition from pediatric patient to independent adulthood.

This is the tenth in a series of guest blog posts by Rachel. Catch up on her earlier posts here.

“The first funeral I ever attended was at 12 years old. We had had similar tumors and were the same age. I had so many questions. Why did her tumor keep coming back when mine didn’t? Why was I still here and she was gone? Why did her family have to grieve the loss of a young daughter? ”

I feel like I must make this crucial point again and again to make sure it hits home: The medical and psychosocial needs of long-term survivors don’t simply go away because we’re out of immediate danger of dying.

The physiological, sociological, and psychological issues of survivors can last a lifetime. The health complications and late effects of treatment, making and losing friends in the cancer community, family issues, economic stress, dealing with visible and invisible disabilities: These are all things that can affect survivors’ mental health.

One of the big themes in my life has been grief. Survivors have a lot to grieve about. If you think grief is reserved for bereaved families whose loved ones have lost the fight with cancer, think again. Survivor’s guilt is all too common in the childhood cancer community. We make friends with other patients in the community and create deep bonds with them, because they’re the only ones who truly understand what we’re going through. The outcomes of cancer and its treatment are different for everyone - no matter how good medicine and technology get - and we often lose some of these friends along the way.

In my grief and loss class in grad school, we watched My Sister’s Keeper, a movie about what happens to a family as each member grieves in their own way over the teenage daughter Kate’s cancer diagnosis. I have a mixed view of such films, like A Walk to Remember. I still haven’t seen A Fault In Our Stars. Nor have I gone back and watched any more of My Sister’s Keeper after seeing clips in class.

I’m simply ‘over’ this type of film. Sure, I would grieve along with the characters for their loss of the “normal” life they had established by their teenage years. Then I would grieve over the fact that I was so young when I was diagnosed during kindergarten that I hadn’t even begun to form said life. I think I would have just vanished with only extended family grieving over me as I hadn’t even had time to create friendships, much less close ones like the ones in those movies. I may have become one of those token poster children of pediatric cancer that organizations rely on to create sympathy and raise funds, but who knows? I would’ve been dead.

The first funeral I ever attended was at twelve years old. It wasn’t for an aunt, uncle, or grandparent. It was for a friend who had passed away who was my age at the time. We shared the same pediatric oncologist and bonded at the local childhood cancer family camp we attended. You can bet it was a tough situation for me. We had had similar tumors and were the same age. I had so many questions. Why did her tumor keep coming back when mine didn’t? Why was I still here and she was gone? Why did her family have to grieve the loss of a young daughter?

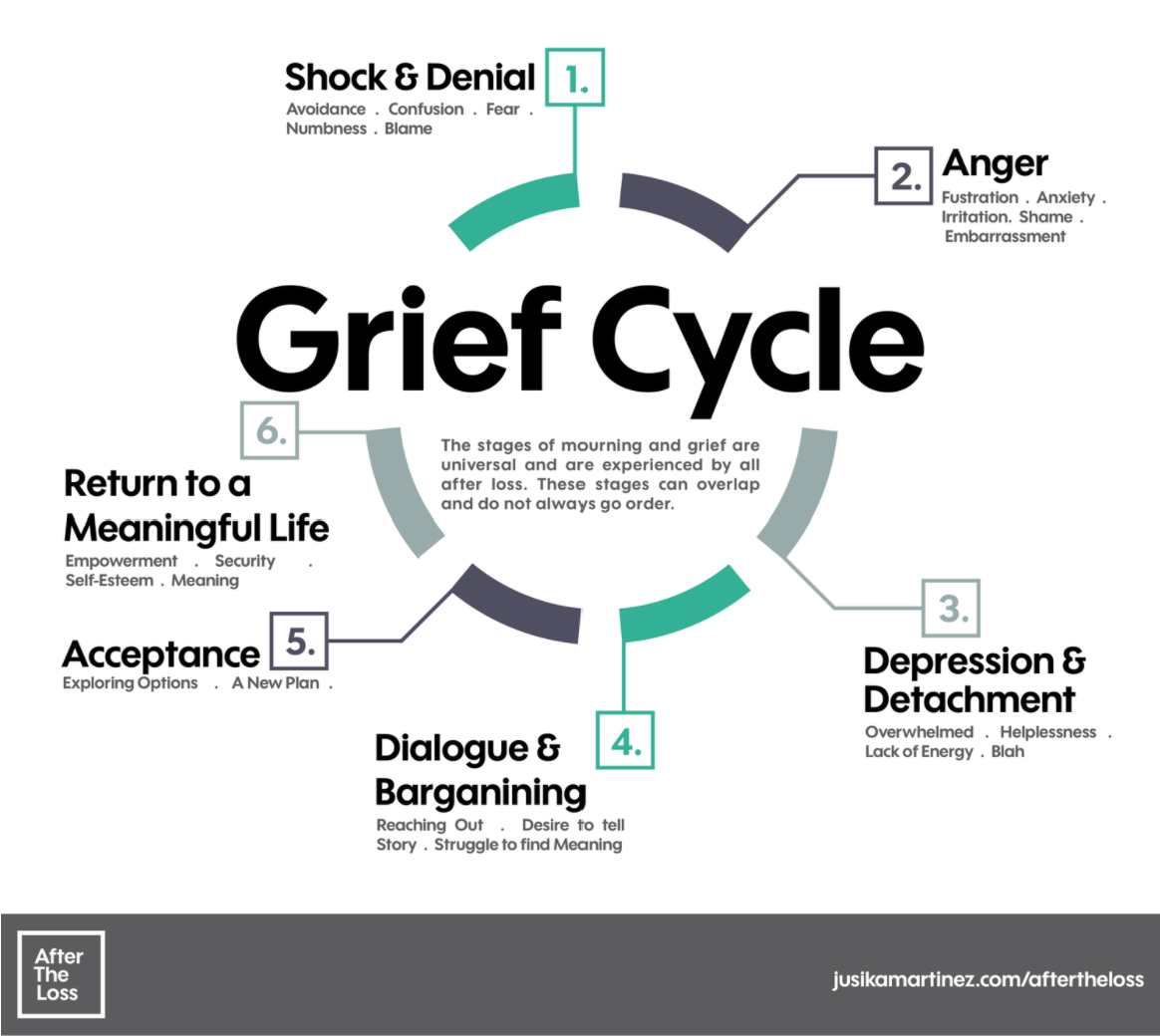

I learned about Kubler-Ross’ 5 stages of grief in grad school, though I’d been familiar with them previously. You’ve most likely heard of them: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. The key to remember is that not all people will go through all stages, and stages are not linear. I myself have had a complex, fluid relationship with the stages of grief over my lifetime. I have mourned my losses - physical, psychological, and social - in different ways over the years.

David Kessler, a colleague of Kubler-Ross, recently added a 6th stage, “finding meaning.” I find this extremely interesting, because I see my venture into social work and grad school as a step along my own journey to find meaning in all the grief I’ve experienced.

I am constantly going through these stages in a sort of cyclical manner. Many may think I am (or should be) “fine” because it’s been so long since my initial diagnosis, but that is not true at all. There has been so much loss throughout my life due to the tumor and its treatment that it’s somewhat inevitable that I have a complicated relationship with grief. Remember that grief is a cycle and may be different for everyone. One does not have to go through the stages in order and can return to a stage at any point.

I myself have experienced each stage of grief at some point in my life. I’ve even experienced multiple stages at the same time in some cases.

My hearing loss journey is an example. I’ve been in shock and denial with regards to my hearing loss while at the same time constantly trying to accept it. I sometimes become depressed, frustrated, and overwhelmed with the difficulties my hearing loss causes daily. At the same time, knowing that my loss is progressive also brings anticipatory grief over someday potentially becoming totally deaf.

I’m constantly also bargaining as I reach out to organizations like the Hearing Loss Association of America in order to find coping mechanisms and techniques for dealing with daily frustrations. Since this is a long-term issue, I have to find some way of accepting my condition and returning to a meaningful life. You could say that my social work journey and telling my story through these blog posts are all part of the latter half of the cycle, if you’re going to number stages.

Add to that the fact that hearing loss is not the only late effect I’m dealing with, and you’ll understand why survivors like myself have myriad reasons to be in an endless loop of the grief cycle. We may be mourning the loss of certain senses or bodily functions, family or close friends (whether physically or emotionally lost to us), a “typical” life (if there is such a thing), or independence as we rely on parents, relatives, or caregivers for basic needs.

Survivors often experience what might be considered complicated grief because we aren’t simply grieving the one-time loss of a loved one. Rather, we’re grieving many things that collectively may lead to a loss of self-esteem. The example at the link above focuses on the death of a loved one, but the same principles can be applied to the complex losses survivors experience.

The symptoms of complicated grief can lead to serious mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and in some cases PTSD.

Depression and anxiety are reoccurring players in my life. I have a considerable amount of long-term anxiety related to an unknown future because little research has been done on long term survivorship issues. Specific things I’ve had anxieties about for a while are driving with eye and reactionary time issues and social situations in which my hearing loss becomes a hindrance.

Depression is a reoccurring issue for me because of all the tragic losses that have occurred in my life. Whether they are related to my diagnosis and treatment or not, the bad times seem to hit me hard. I’ve been through so much that each new tragedy seems to be piling upon the rest. As my last post discusses, I’m dealing with all the same losses as other Millennials on top of the losses I’ve experienced as a survivor. It can get pretty exhausting. I have known for years that I officially have major depressive disorder.

On the other hand, I don’t believe I meet the criteria for an official DSM-5 diagnosis, but I definitely have some symptoms of PTSD. I honestly think there hasn’t been enough study into the traumatic effects of childhood illnesses on the psyche.

During grad school I was baffled to learn that the list of ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) did not include life-threatening childhood illnesses at all, considering how much my tumor and treatment have affected my life. I guess that just goes to show how privileged I am.

When I asked a guest speaker in one of my classes why childhood illness wasn’t important enough to include on the ACEs list, it was explained to me that those who came up with the list were trying to narrow it down to the things that most impacted ongoing quality of life. The items on the ACEs list include things such as homelessness, incarceration, neglect, abuse, etc.

I must admit, I’ve never had to deal with any of those as a child growing up in a White, middle-class family in Southern California. Just another reason why I’m using my voice to raise awareness about the issues facing survivors today.

My diagnosis, treatment, and the aftermath have caused so much turmoil in my life, but I can still advocate to make things better for those coming after me.